ISSUE 11

IN PRAISE OF TEACHERS

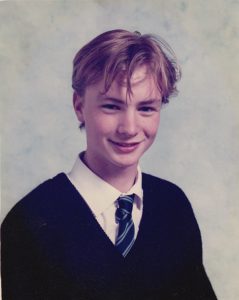

STEVIE RONNIE

While I was learning to write I can remember sitting in a university seminar room with a famous writer who introduced me to the idea that there are some words that should be avoided in poems. When vivid was added to the list of unusable words, I was transported back to my GCSE English class, led by the mercurial and brilliant Mr Currie. The memory that was sparked by this word was of Mr Currie, dressed in a checked shirt and blue woollen jumper and the sort of trousers only a teacher in the 1980s would ever wear. Prompted by a discussion about the book that we were reading at the time, he told me that his favourite word was vivid because it sounded like it felt. He then walked back over to his desk repeating vivid loudly and dramatically, and by conjuring the word into the air he embedded into my memory precisely the thing that he had been trying to explain to me. What would Mr Currie have to say about the banning of this word that meant so much to him? What would Mr Currie have to say about the banning of any word, for that matter?

About a week ago, while scrolling through my news feed, my thumb was stopped dead in my tracks. In among the mindless adverts and the alarmist political drivel that occupies my social media bubble was the news that Mr Currie had died of a serious long-term illness. I clicked the link and discovered that he had been 58 and I’m not ashamed to say that reading this moved me tears.

It had been 25 years since I had seen Mr Currie, but we did have a brief email correspondence shortly after I returned to live in Hexham, the small Northumbrian market town where he had taught me all those years ago. I had contacted him to let him know I was living there again and that I had become a writer. He was still working at Queen Elizabeth High School having been appointed to the post of Head of English. He told me that he knew about my being a writer already, and that he had been following my work and reading my books. He told me too that he had enjoyed them and that he would like to read more. There was a certain pride that I knew he felt towards my publication that I could sense bursting out between the words of his reply. We exchanged a few more emails and talked about the possibility of me visiting my old classroom, to share my wisdom with the latest cohort of teenagers he was working with. For some reason, funding issues I think, this never materialised and when I contacted the school a few years later to chase it up Mr Currie had left to become a priest.

There are few things in my life that I regret, and one of them is the things I failed to say to Mr Currie when we were corresponding with one another. I thought I would perhaps see him again one day and we would sit in the staff room and share a coffee. I would then tell him about how he had inspired me, not only to write and to love words but also to follow my own path and to look for direction in the most unusual places. I didn’t even say thank you and although I am doing this now it feels sad that he will never get to read this.

Mr Currie was unconventional and brilliant. He was more like a friend and confidant than a teacher and I am sure that none of his methods are ever taught during teacher training. One of his qualities was a certain selflessness, although he would be open and honest he never let his own opinions or beliefs lead how he approached a student. I’d had no idea at all that he even believed in god and on hearing he had become a priest, I was at first surprised. After I had thought about it made perfect sense. He was generous and empathetic and he cared for every student, even those who had been cast aside by the system and were destined to fail.

He lived outside the rules: Mr Currie we’re gannin’ for a smoke, we’d say and he’d reply Whatever you do when you go to the toilet has nothing to do with me. Lessons would regularly descend into chaos. We’d be sitting on the tables and drift in and out of the classroom. Pupils who weren’t even in his class would turn up and join in. He never turned anyone away. We didn’t just read Shakespeare, we acted it out, pushing the tables to the edges of the room and losing ourselves in the strange and poetic language of the bard. Everyone respected him and everyone trusted him. Many of the students I know that were taught by him exceeded their academic expectations. He would lend you lunch money without question and never ask for it back. Occasionally, he’d become stern and raise his voice. This would only last for about five seconds before he would laugh and hold his hands up in surrender to the chaos around him. Whenever he really needed us to work, we did; gladly and without fuss. How he got away with any of this I’ll never know.

Yesterday, his funeral was held in Hexham Abbey, a grand 7th century monastery overlooking the town’s market square. There must have been hundreds of people there – they had to turn some people away for lack of space. The high school was closed for the day as a mark of respect. I like to think he would have laughed at my arriving late, much as I used to for his lessons, although in those days I’d have been reeking of tobacco after an extended stay at smokers’ corner. There was a remarkable range of ages there and it was moving to see the sheer numbers of people that had been touched by this great and humble man. I cried discreetly and was overwhelmed; partly by the regret for what I had failed to say and partly because he had shown me that teaching was not just a profession, but an art that went deeper than the curriculum and exams. It was about giving and, at its best, it should treat each student as an individual with potential to grow and develop. He taught me not just the things that he put in front of me but also how to teach, a gift that I am determined to pass on.

Now, for me at least, it is too late but my hope is that somebody reading this might also have a teacher that was just as inspirational in their life. I think that most do – but because we move on we never get to say. If you can think of someone then perhaps you could send them a message, give them a call or, better still, write them a letter. As I have just discovered, you never know when the chance to do that will be gone.