ISSUE 18

Lydia Hounat

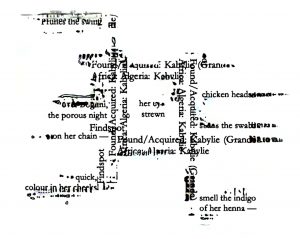

This work began with the perspective of artefacts inside the museum, considering their predicament of being unable to speak. The object at the heart of this work is a Kabyle Azrar from Tizi Ouzou, Béjaïa in Algeria. ‘Azrar’ means ‘necklace’ in taqbaylit. I wondered what this Azrar might be able to say to its audience, if it had one. Unfortunately, it is not currently on display. What might it say to the curators, to the archivists, the cleaners at night? What conversations did it have with its former wearer? How did they wear it?

The necklace generally rests on a part of the body so intimate and vulnerable; perhaps just across the carotid artery, the clavicular bones, at the apex of the sternum. An erogenous zone, and yet fatal, if severed. Necklaces guard and adorn this area, facing its company and any observer in its presence. They sit with the constant pulse in the wearer’s flesh. They are sometimes so inextricably bound to us, that we are buried with them. How much then, do necklaces know and recognise in us? How much did this Azrar experience with its wearer prior to its acquisition in the British Museum?

The Azrar known as ‘Necklace’ in the British Museum’s digital archive is categorised under the number ‘Af1974,06.1’ and was purchased from a Mr Anthony Jack in 1974, a vendor to the museum in the late twentieth century. Any other details behind the Azrar’s acquisition are unknown. But more pertinently, the records for the Azrar stipulated on the British Museum’s website are littered with errors, historical inaccuracies and rather reductive commentaries on its origins. For example, the British Museum refers this Azrar as merely a ‘Necklace’, ‘Made by Berber’, a derogatory name originating from the Greek word ‘barbaros’, meaning ‘savage’ or ‘barbarian’. Historically ‘Berber’ was a catch-all term used by the Greeks and later the Romans to describe any indigenous person or persons living on the land they seized and conquered. Therefore, the Celts were ‘Berbers’ as much as the Goths and therefore the Kabyle people, who made this Azrar, and are part of the wider indigenous Imazighen of North Africa.

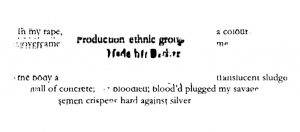

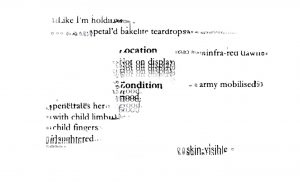

Such theft and ignorance are part of the making of museums. Where we were divided from these artefacts of our heritage with no recourse from the British Museum, I thought to hand their words back to them — without permission. These corroded visual poems plagiarise fragments from the British Museum’s records, appearing indistinguishable from the poetry, which has been partially ‘digitally smeared’. The poetry itself is voiced by the Azrar, which has experienced all manner of rituals in and out of the museum, from mealtimes to photoshoots, first menses to conservation cleans, from sex to sexual violence. In its forced removal from its origins, this Azrar sustains its continual violation, divided from its Kabyle woman, and from the North African elements from which it was made.

This Azrar became the impetus for greater understanding and connection to my roots, to my grandmother, to the sexual violence sustained by Kabyle women, witnessed by the same jewellery I have worn in and out of Algeria, with its own lineage of Kabyle women, whose necks and ears were indented with the same stories and colours. Whilst this work is a huge, unapologetic, solemn ‘Fuck You’ to the British Museum, it’s also a set of confessions and insights into a world and a community that long predates all of its colonisers, which still continues to flourish and be.

TW: This work contains themes of sexual violence which may upset some readers

hear the walls sweat; vault-breath and oily

in my rape a colour overcame — some time

after they milked the Mediterranean grey

tongues of red calcite bucketed with longswords

and fig-shaped grenades. My rigid pus oozing

out of the sides; my pierced ears shrivelling,

shredded lozenges — the body now a translucent sludge another kind of wall, of concrete; bloodied,

blood’d plugged my savage. I know at night their

gloves try to rinse off every colourful scream in the sink, sponging salt penetrating the dust, to polish away

where the semen crispens hard against silver.

her nose hangs over my Tikeffsit, breath

fogging the viewfinder, it finds its humidity

speckling the blue porcelain — a lens-sky

‘Like I’m holding it, am I holding it right?’

a quivering nod before the ends of the chain split,

a white flashback guns me down; cloth-army mobilised penetrates her with child limbs, child fingers, un-daughtered

I come to: my legs spread, on an infra-red dawn a Nikon F ricochets against my belly — the backdrop bedsheet-ready, we do this again, and again,

the boudoir of archive-rape suckling from all the angles in which I have no posture.

He prunes the swing of Ufni

over the mountains of Beni Yenni

their beans urinate the soil —

body on body, their colour goes

around my neck while in Boghni

our grandmother boils chicken heads

in brass pans, her eyes strewn, unravelling purple’d irises twinkling in cumin

until the hour before bed, where

he finds her and foists her Azrar

fingers her with it until she is blue

(so one day his grandson can take the swab of thumbprints on her chain)

quick, colour in her cheeks! —

quick, smell the indigo of her henna! — quick, the pans are boiling over!